Tracing Architectural Pessimism: A viewing device

2019Since 1974 Venice has preoccupied the nature of my work… I suspect in these past four years my architecture has moved from the “Architecture of Optimism” to what I call the “Architecture of Pessimism.

— John Hejduk. Mask of Medusa: Works, 1947-1983, ed. Kim Shkapich, intro. by Daniel Libeskind (New York: Rizzoli, 1985): 355.

What Hejduk means by architectural pessimism and how it is constructed in the drawings of Participant of Refusal is not a pessimistic sentiment but a realization of the death of architecture and an attitude to break away from it by rebuilding architecture with tactility. Drawing is more than what is physically drawn or literally seen. Graphic elements, such as texture, stroke, projection, shades and shadows create a spectrum of viewing experiences, from the literal to the imagined and the conceptual, that may prompt the audience with a deeper understanding of the work. In essence, Hejduk uses drawing to foreground the lost sensuality, or tactility specifically, in architecture. By creating spatial entrapment, constructing mental confusion, and deliberately accentuating weight in drawing, Hejduk is able to arouse tactility through a visual experience.

The design proposal for the display of a drawing of the Participant of Refusal, the house view of 12 one-point perspectives, intends to restate Hejduk’s architectural pessimism. Although not included in the final display, the proposal was for the exhibition, John Hejduk: Double Poetics, to be held at the Power Station of Art (PSA) in Shanghai in July 2021 . The design proposes a spatial arrangement and a viewing device for the drawing in order to create conditions of entrapment, confusion, and tactility in the process and the result of viewing.

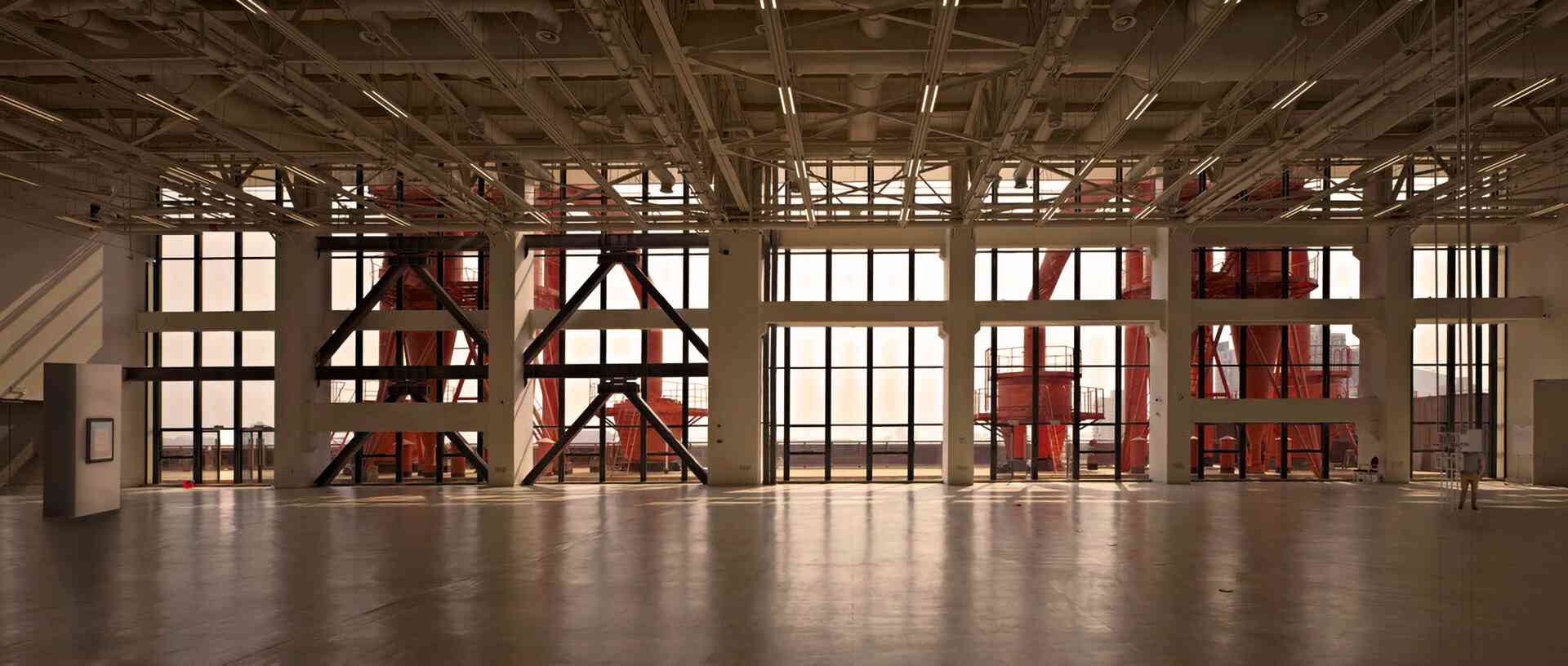

PSA was originally built in 1985 as the Pavilion of the Future and renovated and expanded in 2011. The building incorporates elements of industrial buildings: huge orange industrial pipes are right at the window; trusses cage the atrium space; a tall chimney space is surrounded by continuous spiral staircases. The usually close distance between the visitor and these architectural elements induces an emotional impact. Such close distances were present in an interview with Shapiro when Hejduk sat in front of the back of a clock, a building scale clock of his Cooper Union renovation project.

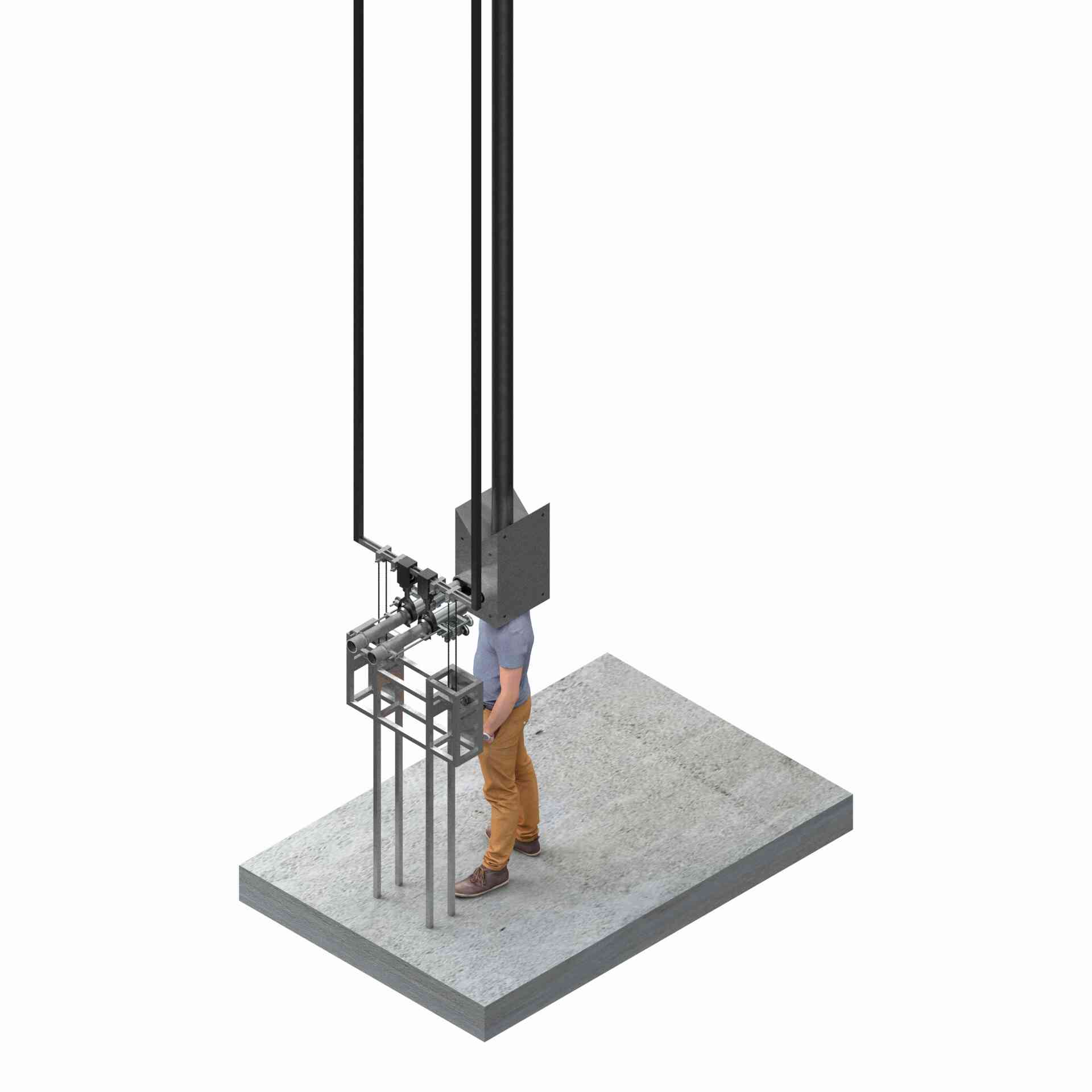

The display is located in an open exhibition area on the seventh floor. This rectangular area is open on one long side with windows facing orange industrial pipes. The other long side has two entrance doors; the short sides are solid walls. The house view of 12 one-point perspectives is installed on the wall on one end of the room; the viewing device is 42 meters away on the other end. When the audience enters the room he/she will be presented with the overall dynamic of the display: the original piece, the viewing device from a distance, and the orange pipes “watching” what is happening in the room.

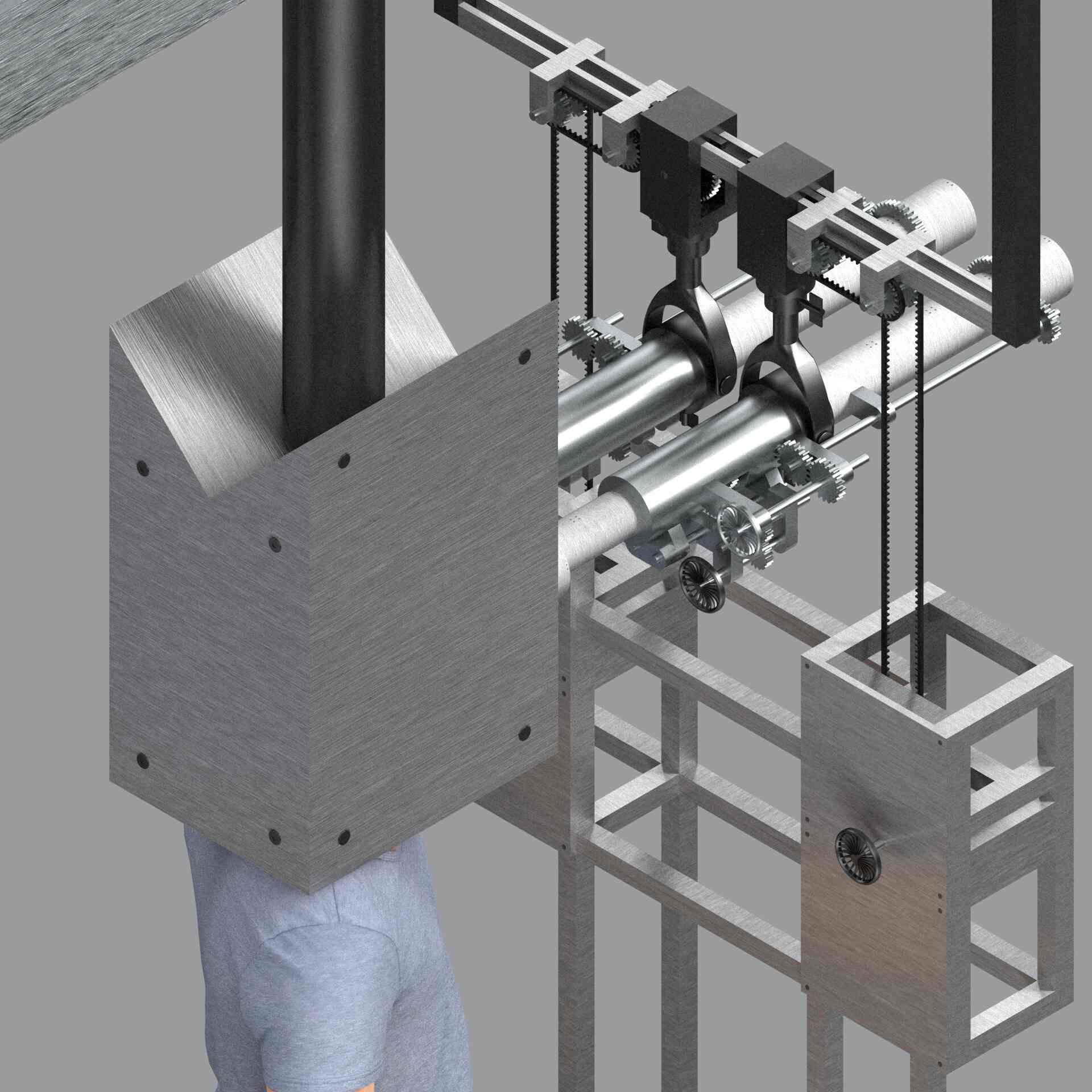

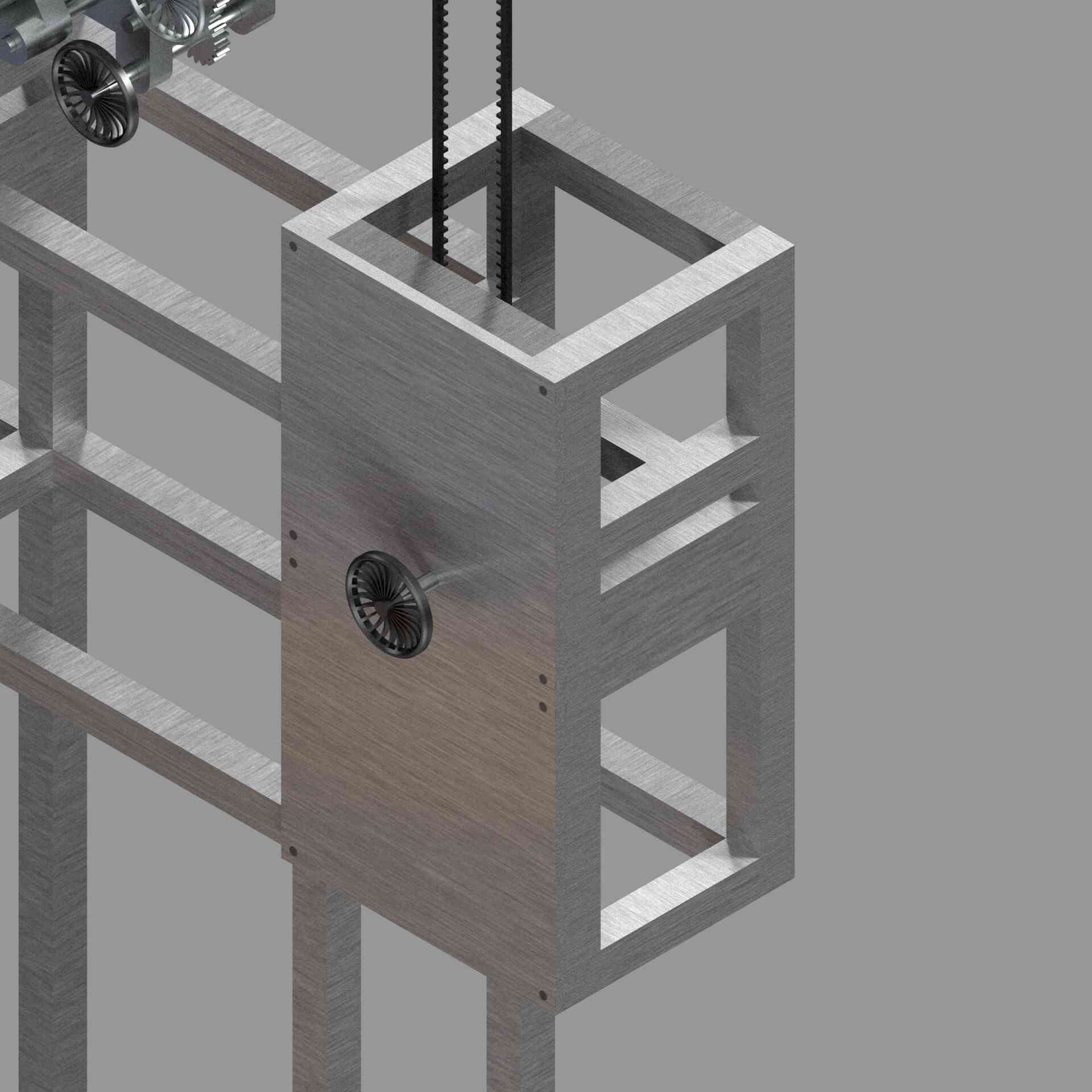

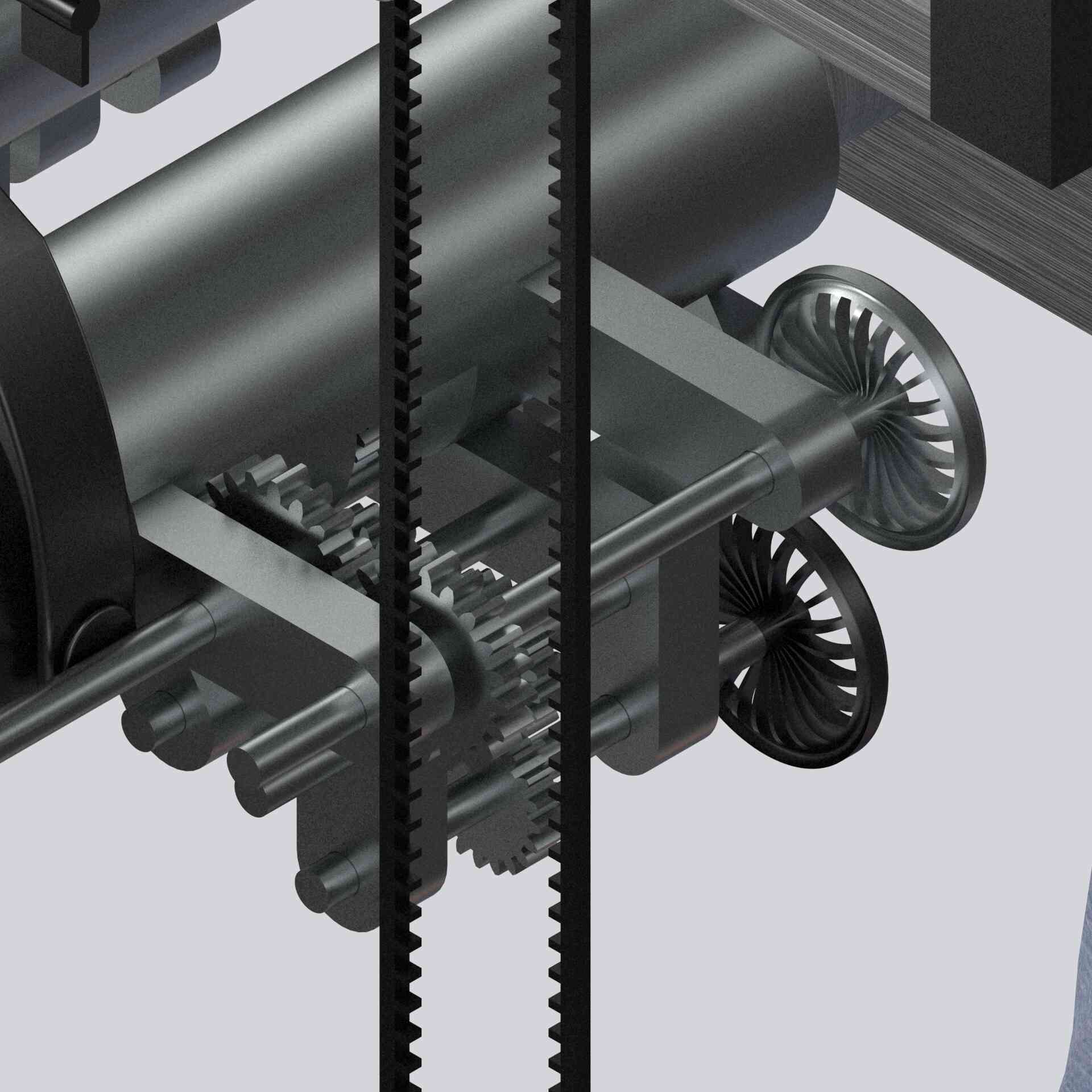

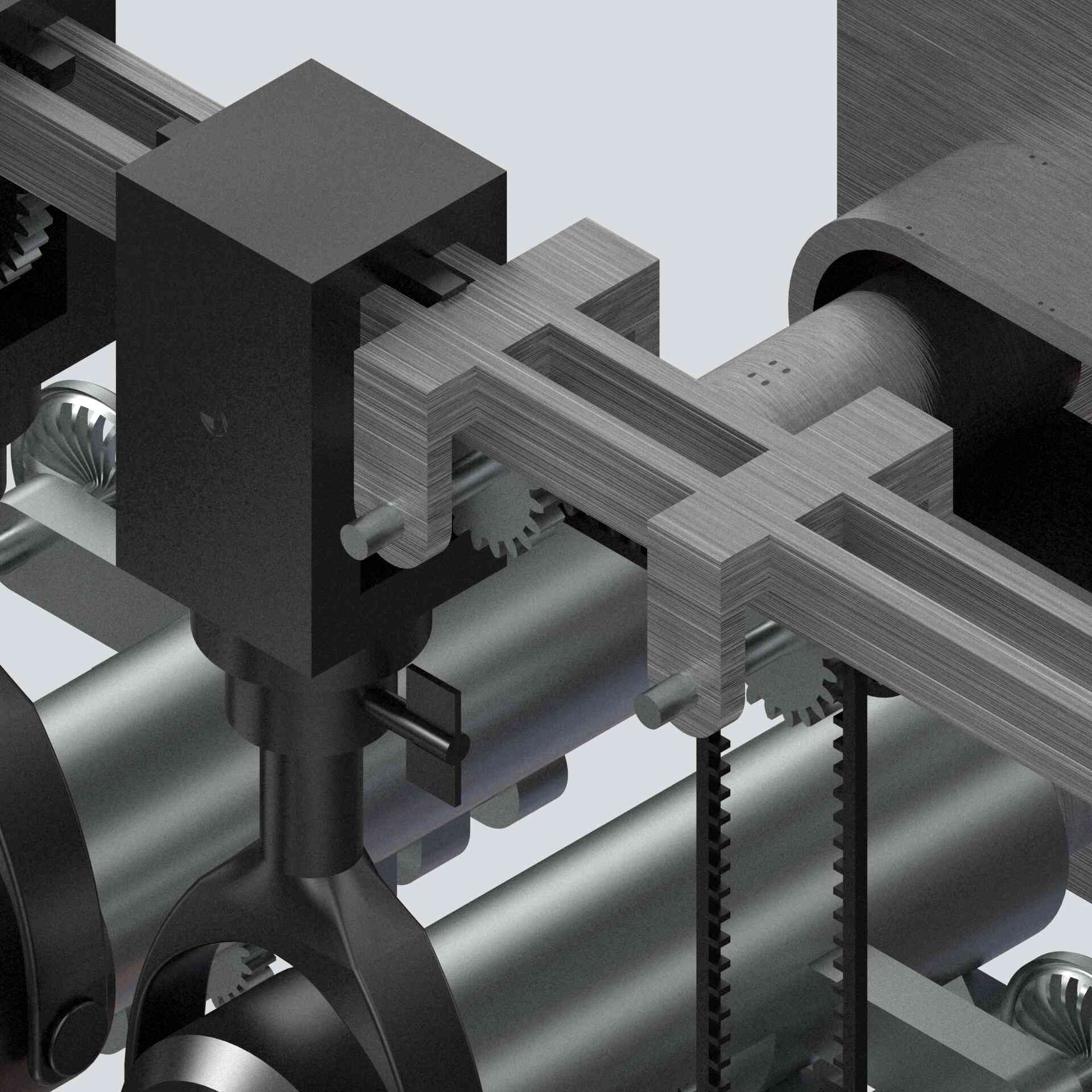

The device is composed of a helmet/mask, two individually-operated monoculars, and a primitive mechanical system with knobs. The geometry of the helmet/mask adopts that of Hejduk’s Kreuzberg Tower in Berlin. The inverted pitch roof points at the audience’s head. The audience needs to bend his/her body in order to get into the device but only the head is enclosed. Monoculars are at 4 feet from the ground so that most audience would need to bend their bodies when viewing. The knobs are 40 inches from the ground.

The audience turns individual knobs to fit the monoculars to his/her eyes; pan, zoom, and focus to look at specific parts of the drawing. The straight view with both monoculars focused is at the center of the empty room of the house where the inhabitant can look at himself reflected on the mirror across the campo. However, since the two monoculars are independently controlled the audience’s two eyes may stare at different spots of the drawing. As the brain struggles to coordinate the views from both eyes the audience can be perceiving an overlap of two different images. If lucky, the audience manages to focus both monoculars on the same spot of the drawing, he/she will be able to zoom in and discover the drawing at a microscopic scale.

The viewing device intends experiences of entrapment, confusion, and tactility. The audience’s head is trapped in the helmet/mask. The literal tactile experience of the fingers turning knobs is disconnected from the visual experience of the eyes. However, it is the tactile experience that is determining the viewing process. The confusion arises from the separate knob’s effects on the views as well as the difficulty in matching the two views of the monoculars. However, when the two views match, the audience can appreciate the unusually close-up view of the texture and the marks of the drawing. The changed scale of these normal drawing materials suddenly establishes an intimate relationship with the audience and regain tactility, in the same way as John Berger’s description of the lilac reflected in his shaving mirror. Essentially, the design is based on the metaphors of viewing. The choice of the monocular is associated with viewing glasses in a theater and spotting glasses in hunting. These associations expand the audience’s role as a viewer from mere visual discovery and hint the social meaning of a spectator, which ties back to the program in Participant of Refusal of the citizen observer viewing the inhabitant.

References

- Abercrombie, Stanley. “Big in the ’70s: Architectural Drawings.” AIA Journal, 69, no. 1 (January 1980): 60-63.

- “Art: Architectural Drawings: The Grace of Fine Delineation.” Architectural Digest, 35, no. 2 (March 1978): 78-83.

- Baensch, Otto. “Art and Feeling.” Reflections on Art. Edited by Susanne K. Langer. London, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Constantine, Eleni M. “John Hejduk: Constructing in Two Dimensions.” Architectural Record, 167, no. 4 (April 1980): 111-116.

- Dienstag, Joshua Foa. Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Greenspan, David A. “Medieval surrealism.” Inland Architect, 25, no. 2 (March 1981): 10-29.

- Hays, K. Michael. Sanctuaries: The Last Works of John Hejduk. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2002.

- Hejduk, John. Mask of Medusa: Works, 1947-1983. Edited by Kim Shkapich. Introduction by Daniel Libeskind. New York: Rizzoli, 1985.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense.” The Portable Nietzsche. Trans: Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin Books, 1968. 42 - 47.

- Pommer, Richard. “Structures for the Imagination.” Art in America, 66, no. 2 (March/April 1978): 75-77.

- Stern, Robert. “America Now: Drawing Towards a More Modern Architecture.” Architectural Design, 47 (June 1977).

The curators of the exhibition are: Yung Ho Chang, Ge Ming, and Weiling He

"Perspective for the House for the Inhabitant who Refused to Participate", by John Hejduk, 1979 (source)